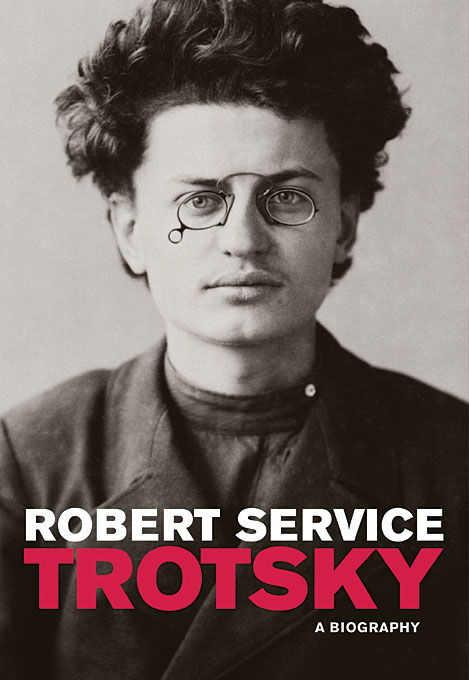

Westerners sympathetic to the ideals of socialism have often speculated about the development path of the Soviet Union if Leon Trotsky (1879-1940) and not Joseph Stalin (1878-1953) had served as Vladimir Lenin's (1870-1924) successor. Taking Trotsky's post-exile criticisms of Stalinism at face-value, radicals such as Isaac Deutscher and Max Eastman have argued that a Trotsky-led regime would have been non-bureaucratic and humane. Robert Service, professor of Russian History at Oxford University, counters such speculative thinking with his new biography on Trotsky. Coming after his previous biographies on Lenin and Stalin, Service claims that Trotsky is the "first full-length biography of Trotsky written by someone outside Russia who is not a Trotskyist" (xxi).1

What makes Service's account different from earlier, well known biographies of Trotsky is that its focus is not on the intellectual meat of Trotsky's voluminous political writings, but rather on the often surprisingly mundane aspects of his personal life. Believing that it is "in the supposedly trivial residues rather than in the grand public statements that the perspective of his career is most effectively reconstructed" (5), Service uses previously unearthed family letters, party and military correspondence, confidential speeches, medical records and the first draft of Trotsky's My Life to reveal the "real" Leon Trotsky, a self-centered man whose authoritarian impulses bear a striking resemblance to that of Lenin and Stalin.

Unfortunately, Service's approach is only partially satisfying. The book's best section is Part One, which covers the years 1879-1913 in rich detail. Service expertly chronicles the path of Leiba Bronstein (Trotsky's given name) from his agricultural Jewish family near the Black Sea to his time with the Shpentsers, the cosmopolitan family that introduced Trotsky to high culture while he attended St. Paul's Realschule, a German institution considered to be the second best in Odessa, and on to his early revolutionary work in Nikolaev, arrest in January 1898, marriage in Odessa prison to the Marxist revolutionary Alexandra Sokolovskaya (1872-1938) and eventual deportation to Siberia. In 1902, after reading Iskra, the Marxist newspaper edited by Lenin and Georgi Plekhanov (1857-1918), Trotsky fled Siberia for Switzerland and London, where he met the paper's staff.

Establishing himself among European socialists, Trotsky later befriended the independent Russian Marxist Alexander Parvus (1867-1924) and fell in love with his life-companion, Natalya Sedova (1882-1962). Quickly returning to Russia during the uprisings of 1905, Trotsky distinguished himself by being the only leading member of the Russian Social-Democratic Workers' Party who was actively involved with the Soviets in St. Petersburg (94). Although Service clearly lists the external steps of Trotsky's transformation from idealistic youth to mature revolutionary, one wonders about the unmentioned internal dimension. What specifically motivated Leon Trotsky?

Service's refusal to seriously grapple with the intellectual rationale behind the actions of his principle actor becomes increasingly problematic as the book progresses. Surprisingly, the weakest sections of Trotsky are Parts Two and Three, which cover the eventful years of 1914-1919 and 1920-1928. Here, Trotsky's shifts in tactics and changes in alliance between Lenin and Stalin are presented as little more than maneuverings for power. Unable to seek or accept advice, Trotsky first pursues an independent policy among Russian socialists by origins.osu.edu, inadvertently earning the suspicion and hostility of his peers (119). Then, in September 1917 he joins Lenin's Bolsheviks and helps direct the October Revolution. Afterwards, Trotsky and Lenin briefly become "the Siamese twins of Russian politics… joined at the hip in their determination to use ruthless measures including state terror against enemies" (190). Sadly for Trotsky, his role among the party elite begins to wane after Lenin's death in 1924. Despite being aware of his weakening position, Trotsky's arrogance makes it impossible for him to lead an opposition to Stalin's rule and he is expelled from the party in 1927. Because party debate to Service is nothing but a masquerade for individual power politics, he makes little attempt to go into the arguments used to justify these policies. The result is a superficial retelling of the Russian Revolution.

Thankfully, Service's account improves noticeably in the final section, which covers Trotsky's years in exile, from 1929 until his assassination in Mexico in 1940. During this time Trotsky published his Byulleten oppozitsii and founded the Fourth International. Free from the constraints of government, Trotsky could easily criticize the Stalinist regime for its failures. Service is correct to write that such criticism was often self-serving and dishonest. For example, Trotsky condemned Stalin's squelching of inner-party democracy, yet Trotsky had joined Lenin in denouncing factions at the Ninth Party Congress in 1920 (270), and reaffirmed the supremacy of the party over the individual at the 13th Party Congress in 1924 (323). Likewise, Trotsky blamed Stalin for the ill-fated union between the Chinese Communist Party and the Guomindang without mentioning his own support for the German Communist Party's failed uprising of 1923. Often, Trotsky's suggestions from exile had few connections to reality, such as when he called for a popular uprising against the Stalinist government by the Soviet section of the Fourth International, even though no such section existed (459), or when he said that Stalin should abandon the policy of "socialism in one country" and spread revolution, without taking into account the violence such a spread would require (394). Service is also right to point out an unresolved contradiction in Trotsky's thinking: namely, if Russia was too backward to sustain socialism on its own, then why had it been right for the Bolsheviks to seize power in the first place (404)?

Service believes that the arguably less-than-honest nature of Trotsky's political writings, the repressive polices carried out under his direction during the Civil War, and the occasional lack of empathy displayed in his personal life, reveal Trotsky's similarities to Stalin in intentions and practice. Trotsky, Service writes, was "no more likely than Stalin to create a society of humanitarian socialism even though he claimed and assumed that he would" (497). Service may be right, but since he gives such short shrift to Trotsky's theories (and even shorter shrift to Stalin's) it is difficult to tell. In any event, this is just as much an un-provable speculation as those Service attacks from people who believed Trotsky could have saved the Soviet Union from Stalinism.

Had the author explored the dominant trends within Bolshevik-styled Marxism instead of focusing on personal exposé, his argument would have been strengthened. But because Service omits these details, his Trotsky tells little more than half the story. One finishes Trotsky wondering why Trotsky became a revolutionary and why millions of Russians supported the Bolsheviks during the Civil War. Readers familiar with Marxism and the theoretical assumptions of key Bolshevik leaders may enjoy Trotsky for the previously unknown personal details it provides, but newcomers are advised to begin their study with the more thorough biographies of Trotsky by Eastman, Deutscher, or Broué.

1 Perhaps Service felt the biographies of Trotsky by Ian Thatcher (2003) and Geoffrey Swain (2006), each less than 300 pages, did not qualify as "full-length."